Billie Zangewa’s tapestries are a tribute to the power of love, family life and the strength of a woman. As a fellow black woman, we explored the intricacies of the experiences behind her work, which allowed for an authentic conversation on art, self-preservation, and re-weaving our futures.

Read the full interview on Harper’s Bazaar here.

When Billie Zangewa and I start talking, I feel that instant sense of sisterhood and kinship that often takes hold when Black women gather during times of despair. It’s the same emotion I experience when I look at her work as an internationally renowned textile artist, in which she creatively represents what it means to be a Black feminist mother raising a young son in today’s climate.

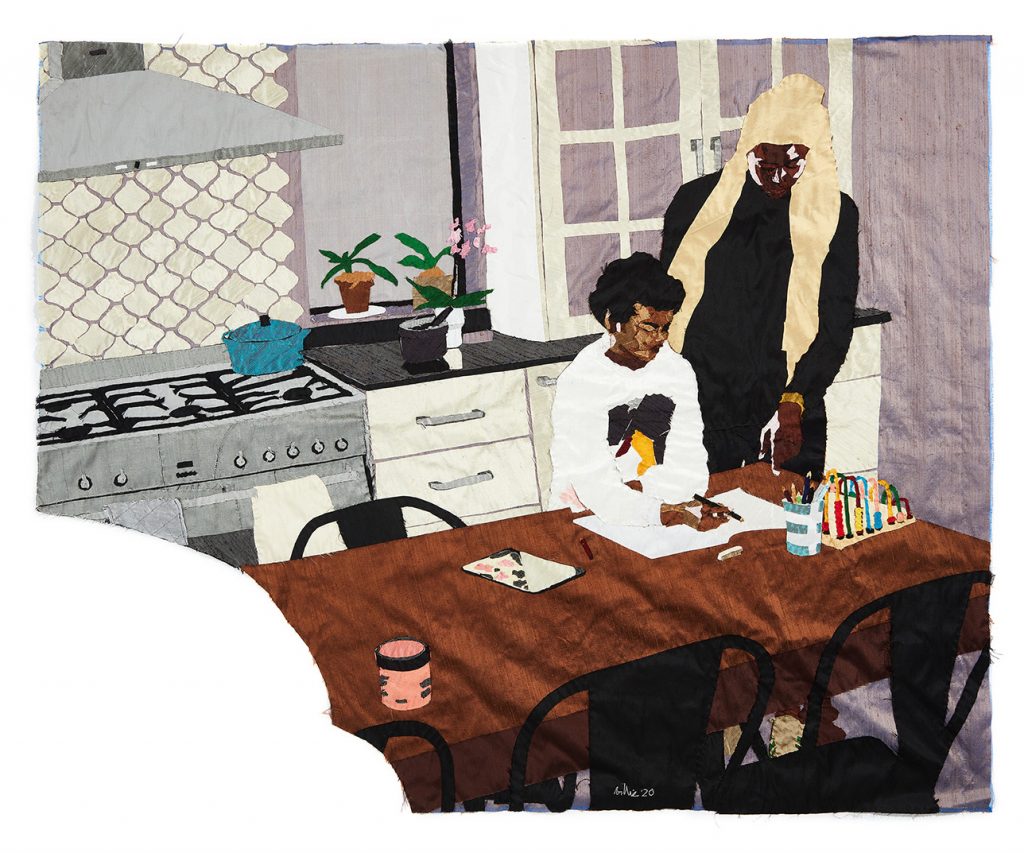

Using a mix of silk – her signature fabric – and sustainably sourced scrap materials, Zangewa creates large-scale tapestries that portray scenes from her everyday life, from reading on the sofa in In My Solitude to walking her son to school in Soldier of Love. By weaving these visual narratives, which conjure up a mood of joy and peace, she often equates resistance with self-love and everyday feminism. “In a way, I feel like I’ve been quietly, daily, advocating this movement for ever,” she says of the momentum that has gathered around the Black Lives Matter campaign this year.

Born in Malawi and now based in Johannesburg, South Africa, Zangewa is acutely aware of the differences between the forms of racism faced by Black people across the Diaspora and on the continent. “I am fortunate enough not to have experienced police brutality, but I have experienced the other kinds of limitations that come with having dark skin,” she tells me. To process this – “the anger, wanting justice, all of it” – she has found consolation in the power of love, which for her is a source of “fundamental strength: strength of a person, strength of a family, strength of a community”.

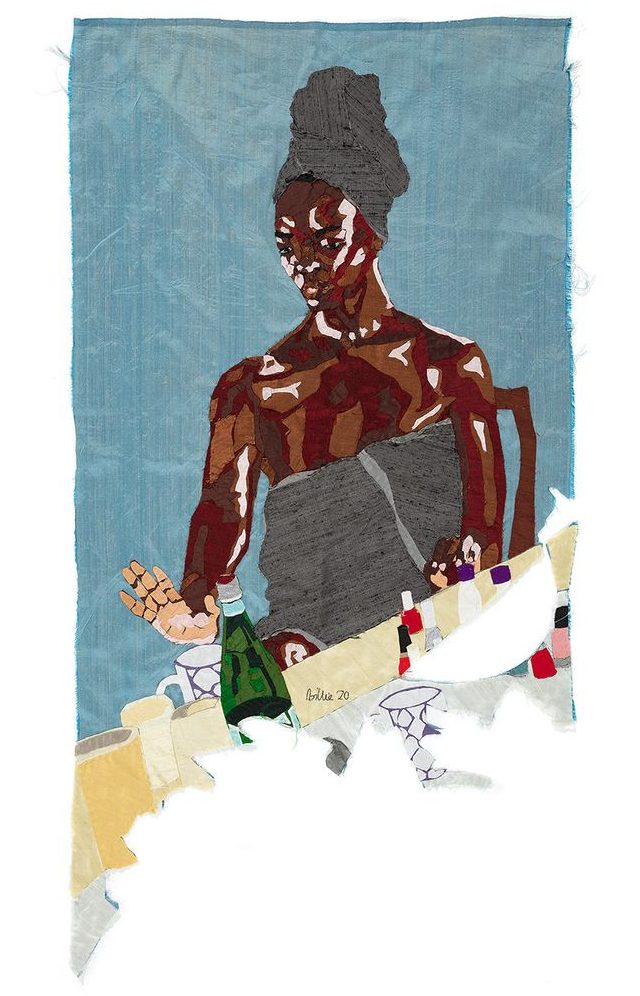

Love is depicted through acts of self-care, as visualised in Self Care Sunday, and in small, meaningful moments spent with her son, as seen in Heart of the Home. In contrast with the pain and suffering we are normally forced to see in images of Black bodies, coined as ‘trauma porn’, Zangewa’s work is a reminder that tenderness and joy can be found in simple, everyday things.

Empowering women is another key catalyst for her work. “It says, here’s a woman whose life is not perfect and who has her own struggles, but she is saying we can do it, we can look to the light, we can look to the positives and use those things to lift us up,” she explains. Inspiration comes from the strong female figures in her life, including her mother and grandmother, as well as from powerful women-centric imagery in popular culture such as Diesel’s 2001 campaign photographed by Ellen von Unwerth. Taking the form of a fictional newspaper called The Daily African, the series depicted Black models in luxurious settings, with headlines imagining Africa’s supremacy as a world power. A similar narrative of women’s independence has come to underpin much of Zangewa’s oeuvre.

This year, like everyone, Zangewa has encountered her fair share of difficulties during the pandemic, including the disappointment of Paris going into lockdown as her ‘Soldier of Love’ exhibition opened at Galerie Templon. “I had just got to my opening as everything closed, even my hotel,” she recalls. Fortunately, the gallery adapted quickly and moved the display online, offering virtual tours for site visitors. The experience taught her to be patient and willing to accept uncertainty. “The biggest lesson for me has been to be open to change, and just saying to the universe that I surrender to your will,” she says.

For a while, Zangewa was concerned that her current show, ‘Wings of Change’ at New York’s Lehmann Maupin, would also have to take place digitally, but in fact it has been able to go ahead in physical form, garnering some superb reviews along the way. The scale of the pieces on display, which range from 81 by 117 centimetres for An Angel at my Bedside to 137 by 100 centimetres for Free Spirit, is made all the more impressive by the fact that each one is hand-stitched in silk. This new collection reflects the radical shifts in Zangewa’s daily routines that have come about as a result of the pandemic: Heart of the Home shows her home-schooling her son due to school closures, while A Fresh Start represents the reinvigorating power of a simple shower.

“Empowering women is a key catalyst for her work”

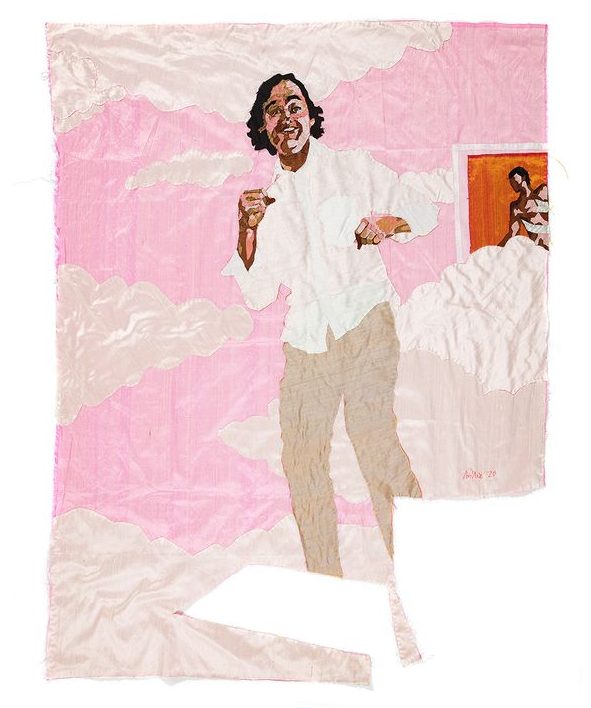

The New York show – Zangewa’s debut in the city – is also a way of paying tribute to her dear friend Henri Vergon, an art dealer who founded the Johannesburg-based gallery Afronova, who died in May at around the same time as she was offered representation by Lehmann Maupin. Having shared much of her twenties and thirties with him (he was, she explains, “the first person I went into the art world with”), she immortalises him in Free Spirit, and sees the exhibition as a way to celebrate life, let go of recent sadnesses and trigger a kind of rebirth. “It’s about looking at things in the past differently from the way I would have looked at them if I weren’t in isolation; about letting go of things we’re in a habit of carrying that no longer serve us,” she explains.

While Zangewa sometimes feels frustrated at being defined by her race in a way white or European artists rarely are, and looks forward to a time when narrow titles such as ‘Black artist’ or ‘African artist’ are no longer needed, she acknowledges the visibility her Blackness gives her. “Maybe this is an opportunity to get to that place you want to be, where you are just simply an artist,” she reflects. Her advice to aspiring artists across the continent or from the Diaspora is clear. “If you want it, commit to it. When the landscape doesn’t look good, believe in it,” she says. “And if it’s not what you really want to do, then I say, get out now, because it requires steel. You have to be strong and you have to have conviction in yourself, what you want and your potential.”

Zangewa’s tapestries offer an intimate insight into life as a Black woman and feminist mother raising a Black son. Despite our collective experience of Blackness, from the traumas and difficulties we are subjected to, we all cope differently, weaving intricate variations from these narratives and thriving against the odds. It is never easy, but Zangewa’s work reminds us that ours is a beautiful life to be cherished.

Images courtesy of Lehmann Maupin