Black culture has remained the bedrock of entertainment, the arts, and culture despite a year full of trauma. With this in mind, I spoke to six creatives on how they have used art to reclaim their narrative, in spite of – and because of – the events of 2020.

This article was originally published on Bustle.com

Many of the disruptive changes the creative sector requires needs to be led by those from disadvantaged communities as they are the ones most affected. However, how do we provide support and nurture those who are in turn experiencing trauma while creating progressive art? We cannot expect the revolution to be as simple as posting a blank photo. #BlackLivesMatter has always been more than just a hashtag – it is a call to action rooted in addressing the injustices that Black people face as the lowest valued members of society. It is also the base minimum of understanding required before tackling other aspects of anti-Blackness, such as our right to happiness, peace, vulnerability.

The start of a new decade held a lot of promise, but little did any of us realise that – in addition to Brexit – we would also face a global pandemic, an anti-racism uprising, the deepest global recession since World War II, and a housing crisis. The UK’s Black communities have been disproportionately affected by each, with racism and discrimination identified as contributing factors in Public Health England reports. And yet, Black culture has remained the bedrock of entertainment, the arts, and culture. We shouldn’t have to be this brave, but from our pain has come power, beauty and strength.

With this in mind, I spoke to six creatives on how they have used art to reclaim their narrative, in spite of – and because of – the events of 2020.

Performance artist, theatre maker, poet, and writer Travis Alabanza

Were it not for the pandemic, Travis Alabanza’s internationally-acclaimed Burgerz – celebrated for the way in which it increases the visibility of, and advocates for the queer and transgender communities in a nuanced, engaging way – would have been on a global tour this summer. Instead, they lent their social following and voice to other causes and grassroot organisations – including Free Black Uni, Colours Youth UK, and No More Prisons – through Hacked. “It was a really creative outlet for me as a way that I could use my practice and skills to be responsive and helpful during lockdown,” they tell me.

Alabanza recognises that some may see their work as rooted in pain, “but I think actually, as a gender non-conforming person, especially one that’s racialised, we experience so much violence every day. We don’t have a luxury to avoid all our violence, and so much of my work is about trying to shift the power dynamics in that violence.” As with Burgerz before it, that is also evident in their latest show, Overflow – a beautiful and brutal tour of women’s bathrooms and the sisterhood that’s often found there.

“For me, performance has agency,” adds Alabanza. “It allows me to create an alternative ending where I’m not harmed or disempowered. The fact that [Burgerz] managed to exist amongst that [violence], and not just exist, but thrive, is significant.”

Writer, performer, and theatre producer Keisha Thompson

“Lockdown has given me more time to reflect,” begins the Manchester-based creative, “and I have taken on social distancing as a creative parameter for creating new work.” As a writer and performer, Thompson has been focusing on offering online performances and workshops, producing short films for her new spoken word, and adding new skills to her artistic repertoire.

“Making a digital show means we’ve been learning loads of new skills,” she explains, “so this time has been about trying to start a conversation with my work and show people a new perspective.”

Although, as the Young People’s Producer at the Contact theatre in Manchester, it has been an especially long lockdown. With Greater Manchester first placed in a localised lockdown at the end of July due to rising cases of Covid-19, the region has been assigned Tier 3 since its introduction in early October.

Mastering new methods also served as a stark reminder of how valuable freelancers are to institutions. “Freelancers are increasingly aware of how valuable they are, as well as how much venues need to do to adjust to working with us. Engagements, performances, exhibitions, etc. will have to be more intimate, unconventional and imaginative,” she says. As her art has evolved during this time with increased value, like many others’, Thompson is a reflection of how artists have diversified their work during this time.

Sustainable designer, storyteller, and Zambezi ‘artchivist’ Banji Chona

The pandemic brought a “sense of stillness and mindfulness, if you will, to my bubble,” explains Banji Chona, though she has missed the “physical proximity to places and people,” she admits. “It has honestly taught me that inspiration is never far or out of reach,” she says, reflecting on her new-found ability to listen to and nurture herself and her surroundings.

Until this year, and COVID-19, collaboration was Chona’s preferred way of working. “Collaboration is like water to a seed. Someone, somewhere will always know more than you do. For the sake of expansion, my art has allowed me to instill particular frameworks to be sponge-like and seed-like, in that I take in a lot, and also shed a lot,” she says of her new approach to creating artwork.

Her Zambezi Artchives project was born of the need to bring accessible, informative narratives of Zambian culture to life. “Though my art, I have been able to facilitate the forging and nurturing of positive, representative and relevant discourse on Zambian art and culture,” she tells me, “as well as the promotion for the deconstructing orthodox archetypes and normative ideologies of African socio-circles.”

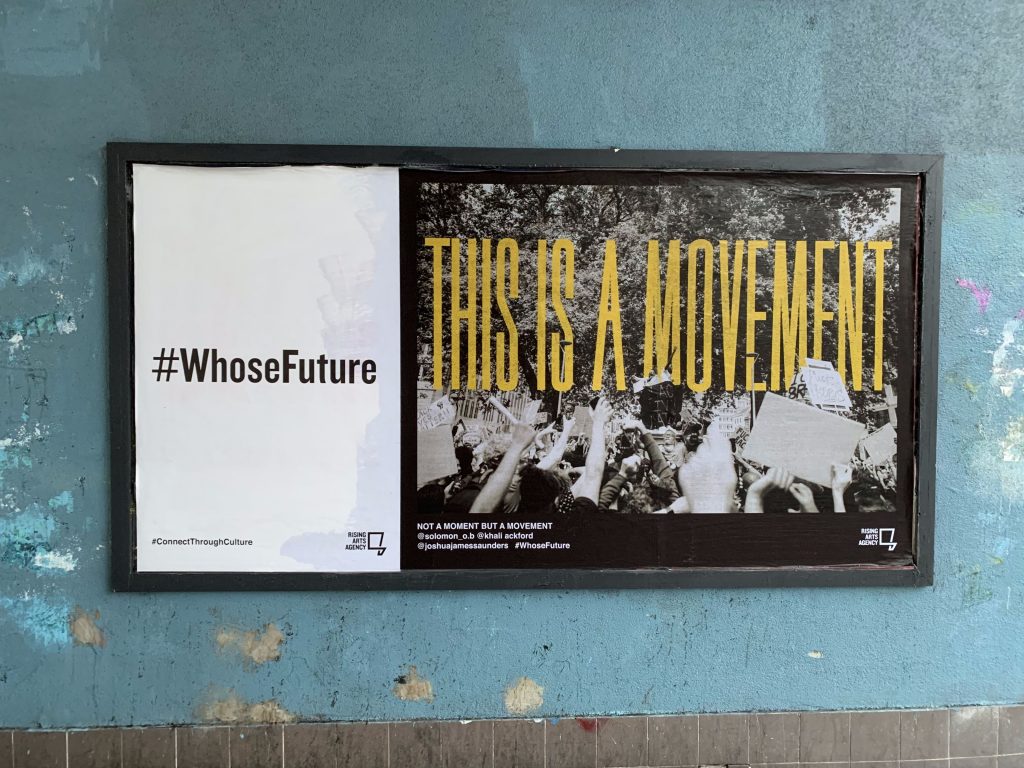

Poet and activist, Solomon O.B

Being Black doesn’t automatically make us activists, but as well as contending with a pandemic, these artists have also considered how their practice could contribute to the wider Black Lives Matter movement. They have used their work to tell their own stories and make their voices heard at a time when Black lives have seen so much trauma this year.

Bristol-based poet and activist Solomon O.B was among the first to speak from the plinth where the statue of slave trader Edward Colston once stood, after it was pulled down during the #BlackLivesMatter march in June.

Solomon is one of those rare souls whose craft is not only a pure embodiment of them, but it can command a space and resonate with thousands even at the most spontaneous of times. Discussing his relationship with words, Solomon shares, “We keep the legacy of those behind us alive through our words and actions.”

Performing at various BLM marches over summer has been a cathartic way for him to process the trauma and express the pain. “My writing has been a way for me to document my own growth during this time, as well as observing and speculating on the wider effects of global events,” he explains.

Once he discovered their power, his poetry became his way of making sense of everything within and around him. “I feel like it’s the role of writers and artists to decode and translate the changing shape of our reality,” he says. “With the world changing shape so much and so quickly, it’s a super interesting time we are living in.”

Photographer and stylist, Arinzechukwu Patrick

This year has shown us the true value that can come from our increased global connectivity. Aware of its potential, art has been a way for these artists to nurture communities and provide opportunities to unify people.

Arinzechukwu Patrick is a photographer, stylist and the founding editor-in-chief of Random Photo Journal, an independent publication on life in Ghana, Nigeria, and Lomé in Togo. His work is a study of the environment he lives in, photographing the flamboyant richness in everyday life from a raw, unfiltered lens.

“I started The Random Photo Journal as a way to focus on African unification,” Arinzechukwu Patrick explains. It does this through forming collective memories and shared connections with those across the continent. This way, it doesn’t contribute to the Western misconception of Africa as a monolithic culture where the uniqueness of each culture and heritage is blended into a blanket symbol. But to achieve this, he recognises the need for global solidarity, adding, “why should we be in solidarity with those protesting #BlackLivesMatter [across the Diaspora]? Because one way or another we are all connected through memories, family, friends or places visited.”

Images from the Random Photo Journal archive and Patrick pictured (right)

COVID-19 has undoubtedly stripped us of our usual coping mechanisms and grounding activities. But for some of us – and for artists especially – the chance to pause and reflect has also been hugely beneficial.

Patrick has used this time to think about the work he has put into the world already. As creatives, we can often feel the pressure to constantly present newness. But there’s so much to be said for the rich heritage and experiences we have already translated into creative visions. For him, this has meant using lockdown to study his extensive archive, ponder on its importance and the various ways to get his art seen by more people.

Through this, Patrick has recognised the role of artists as being part of a wider system. He explains, “my search for honesty in artistry is part of a larger community of artists who are also out there in different cities searching for similar truths through various mediums”. In this way he feels the responsibility to take ownership of his contribution to the bigger picture. “The feeling of being part of something bigger than myself has taught me to not take things regarding my creativity lightly,” he adds.

Illustrator Maya Mihindou

There is a need to raise awareness of, be involved in and support issues across the continent just as much as, if not more than, we consume the culture for entertainment. Likewise, the poor representation of Blackness across Africa and mainland Europe means we are often complicit in and ignorant to the unique experiences they face. Challenging this, French illustrator Maya Mihindou uses her practice to question society by creating dystopian, abstract worlds, which both reflect and distort our perceptions of every-day life. “Towards the end of the first lockdown, I felt like my body was dry of art and nature,” she tells me. “During that time I felt petrified by the craziness of the situation. Drawing permitted me to break my own internal silence.”

Does the cathartic nature of her work mean people’s perception matters to her less? “Obviously, it’s important to me to be able to ‘touch’ people in a way, but my images are purposely not always obvious.” It’s this abstruse edge that makes her work incredibly compelling.

Left: the one who carries the bones; Middle (top-left): Constant decentering; Middle (top-right): Sometimes more skin, thoughts, body. Only the struggling memories. Middle (bottom-left): Body split into three. Fruit of complicated memories the memory and the body-thought separate like oil and water. Middle (bottom-right): So the skin carries the bones and the memory walks side by side

Most recently, it has been the mistreatment of the most vulnerable in her hometown of Marseille that influenced her art. When the state failed to intervene, the local community came together to feed those in need. It became one of the many collective community initiatives that has come from Covid-19, where it soon became all too clear that the reliance on governmental support wouldn’t suffice for the immediate, short-term needs we were seeing in our communities.

“It’s like capitalism is the only muscle we have worked on for decades. We have to work on other muscles, collectively,” she says. “Knowing afterwards that the police will return to the streets of France to hunt the refugees they had left behind during lockdown, most of whom are Black, I feel how important this moment is.”

This year has been a stark reminder that it is our future on the line. It is ours to be disruptive, to claim spaces as ours. To be so political that the whole landscape across all industries is forced to act. The work of these incredible creatives and the millions more of us is a testament to the truth that the message doesn’t need to be watered down for people to get it. It is imperative now more than ever that we come out of this with a new system that values the lives of Black people.